Ditch that “mind strengthening” app you just downloaded because an Instagram ad convinced you to (there are for sure gonna be in-app purchases).

Learn a language, instead.

But what does it mean to learn a language to be able to “speak” it?

“I speak [insert number] languages”

Recently, there’s been a growing cohort of “influencers” who surprise unsuspecting non-English speakers by seemingly speaking their language fluently.

Don’t feel discouraged if they’ve ever made you feel like a dumb dumb.

Here’s why: most of these so-called polyglots are full of total caca.

Some of them are legit. But many claim to know an outrageous number of languages supposedly learned in record time. In the age of hyper-video editing, I’m not buying their alleged “abilities.”

What does "to speak" mean in this context

The real marker of speaking a foreign language is in your competence across the four essential skills – listening, reading, speaking, and writing – aligned with the globally recognized CEFR levels.

This framework provides a clear, measurable standard to assess true language ability.

Here’s how CEFR breaks down proficiency.

The CEFR emphasizes a balance across input and output (listening / reading & speaking / writing). True fluency means you can fluidly apply these skills in real-time, adapting to native speakers without over-relying on translation or rehearsed phrases.

When someone claims to “speak” a language, the question isn’t how many they know but to what CEFR level they can use each of these skills.

So the next time someone says, “I 'speak' [such and such],” hit ‘em back with “what level?” They likely won’t even know this framework (or care).

For your purposes, it suffices to say, “I speak level B1 Spanish,” for example.

Ok Mr. Language Police… what about you?

I’ve traveled to 12+ countries and “speak” 4 languages of varying levels from A2-B2. Admittedly, I've taken no formal test to truly establish my levels, and each language fluctuates as I fall into and out of practice with them.

Spanish – my first love affair with language

Current level: B1

Highest estimated level achieved: C1

Goal: To get my level back up in time. I’m also not in the Spanish-speaking world currently, so it’s not high on my priority list.

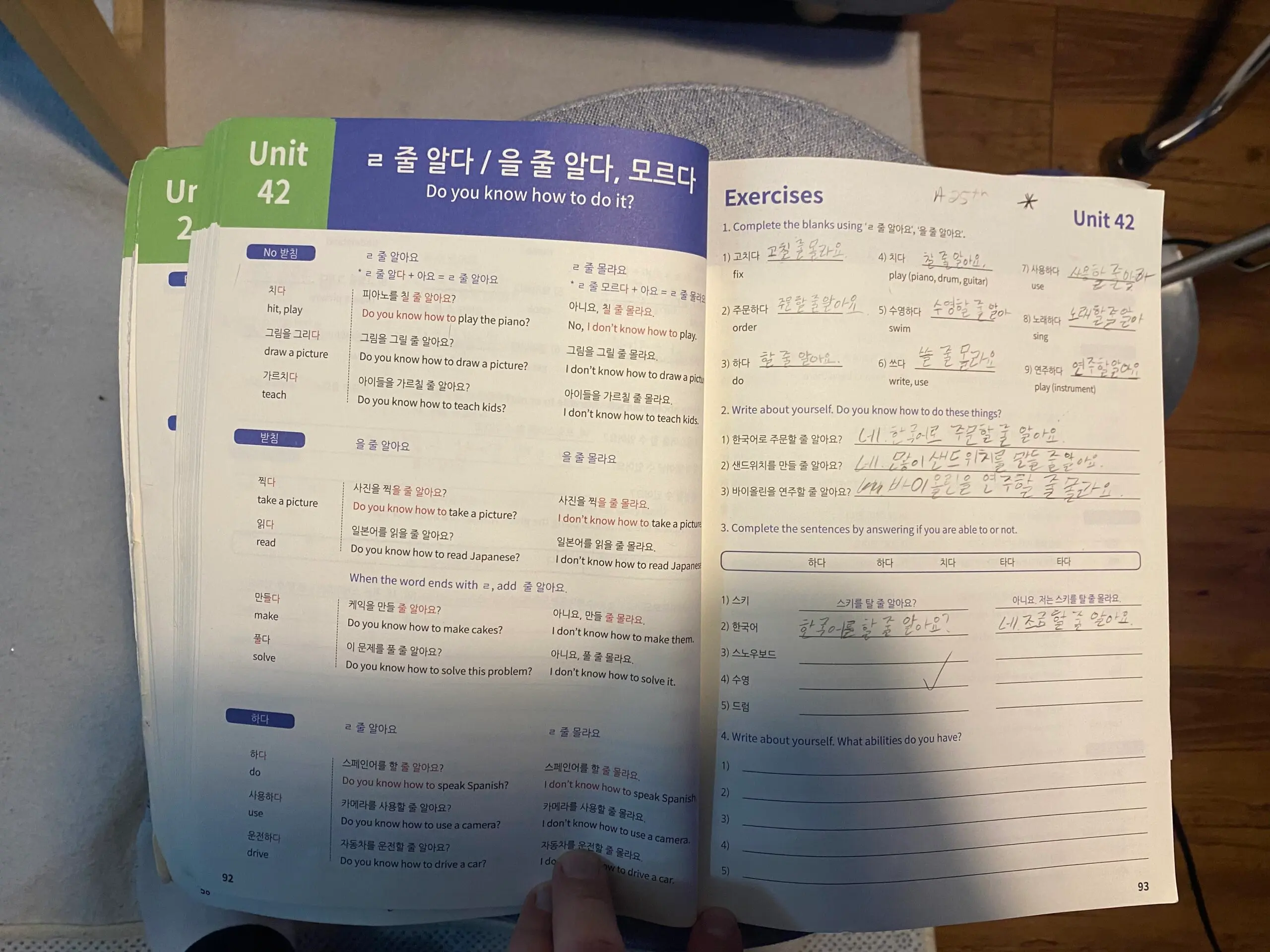

Korean – Had utility, now the future is doubtful

Current level: A2

Highest estimated level achieved: B1 (summer 2021)

Goal: Ideally, a TOPIK level 3 (B1) would be nice. But I'm having doubts of ever returning to Korea, so it may just stay as is.

Italian – I should know more

Current level: A2

Highest estimated level achieved: A2

Goal: I should know more about this because I became a dual U.S.-Italian citizen in 2024. Spanish helps. But given that I’m a citizen now, I must study.

English – Native English Speaking privilege

Level: Native

Goal: To keep improving my writing.

Thinking of Mandarin Chinese

Current level: Couple words

Goal: Undecided but very interested. I mean... it's China. 1.4 billion folks. Ubiquitous. New challenge. Economic opportunities. Traveling there would be kind of taboo and fascinating for an American. (I like taboo.) To be seen. Could be a long, crazy journey to document. Chinese government, sure. But like... you know how many lizard-people work in D.C.?

Should you learn a second language?

Of course, it's your call. But consider this.

Learning a new language makes traveling to a new country and communicating with its people possible without the impersonal "let my phone translate this" crutch, sure. But the real benefit is the new way of thinking. It challenges your mind to process ideas differently than your native language would allow.

I have zero hard data on this, but from personal experience, I feel like it keeps my cognitive abilities sharp – even when it comes to using English more effectively. It helps me appreciate "the why" behind the many English Language concepts.

Italian serves as a great example

I coined the phrase, “What’s formal (in English) is normal (in Italian),” or “What’s normal (in Italian) is formal (in English).” Either way, it’s the same idea.

Litigare – to argue

Translated literally, it’s “to litigate,” which in English is a word only used in legal contexts.

Controllare – to check

Translated literally, it’s “to control,” which is a bit more elevated in English, implying authority or regulation.

Domandare – to ask

Translated literally, it’s “to demand,” a much more heightened and forceful way of asking in English.

Dimenticare – to forget

This would be like turning “dementia” into a verb: “I dementia’d my umbrella.” Kind of funny when you think about it.

Dosso artificiale – speed bump

I saw this on a road sign, and it seemed like an extremely long-winded, formal way for a road sign to say “speed bump.” 7 syllables vs. 2 syllables. Imagine warning a driver of the upcoming speed bump they don’t see, and you have to get out 7 syllables in one second.

Portafoglio – wallet

This sounds formal in English as we might think of a literal investment portfolio, but it’s used in everyday Italian for what we call a wallet.

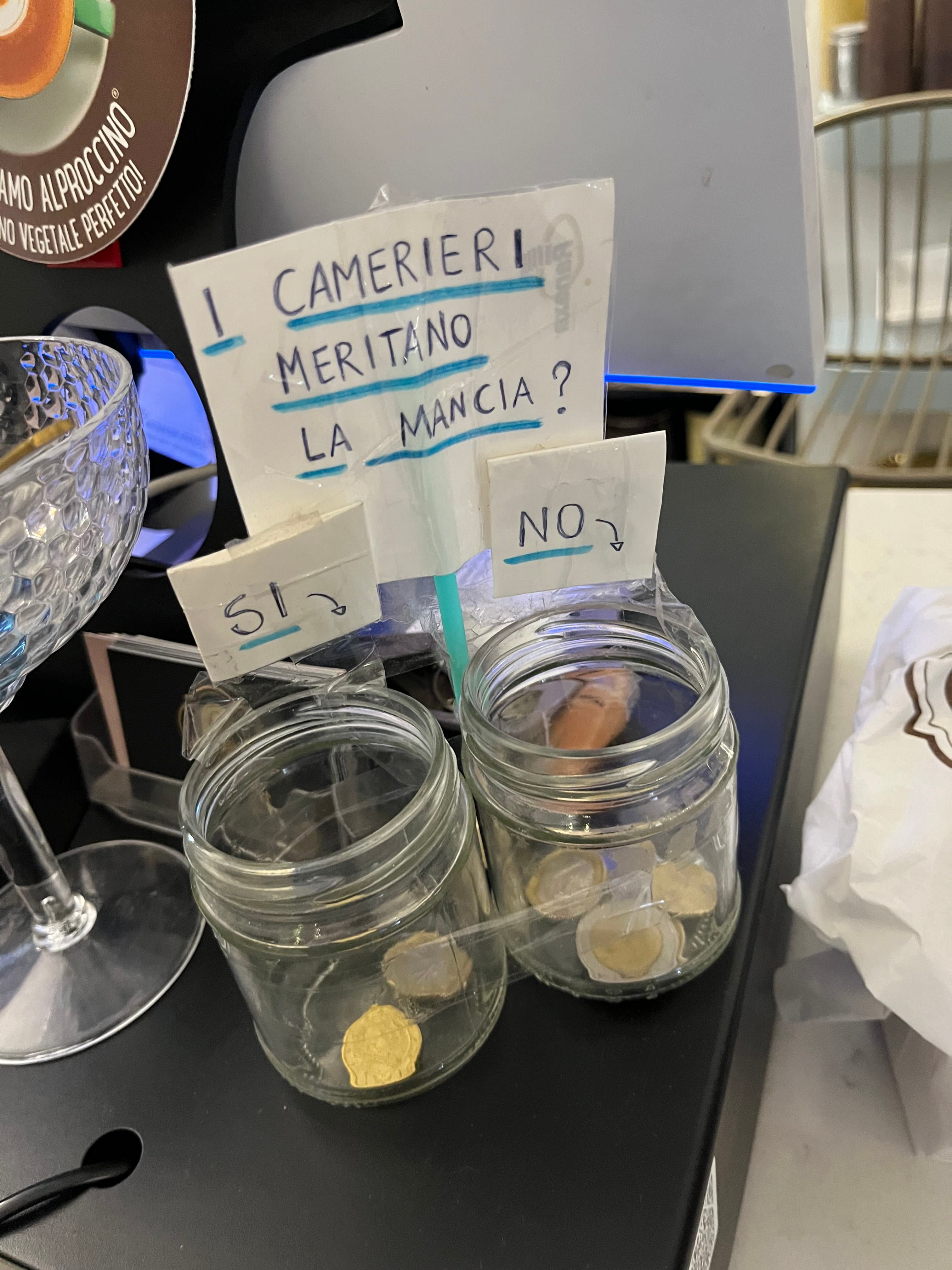

Meritare – to deserve

Translated literally, it’s “to merit,” which in English is a much more formal and rarely used word than the casual, everyday Italian usage.

In my experience learning Italian, I’ve noticed it’s changed the way I think and even helped expand my English vocabulary. When I encounter an Italian word resembling its English counterpart, I can often make sense of it through context.

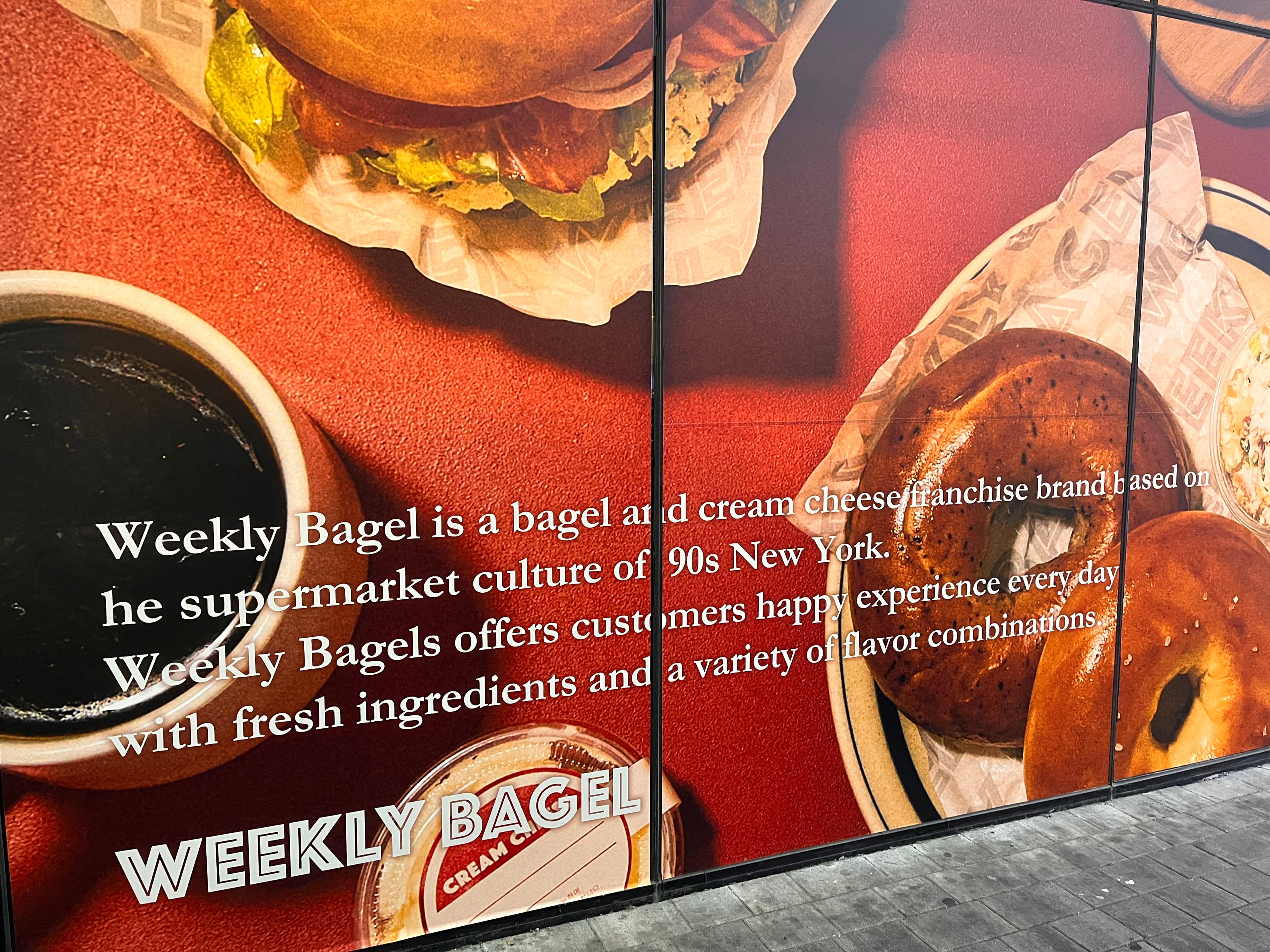

The fascinating world of Konglish

I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about this. I lived in Korea from 2019 to 2022 and just returned from a visit in December 2024.

Apart from Koreans using English in advertisements in absolutely hilarious ways (image above taken Dec. 2024), the concept of Konglish is truly mind-blowing.

Konglish is the (very convenient for English speakers) hybrid of Korean and English, where English words are adapted into Korean phonetics with new meanings, pronunciations, or contexts.

Some are direct borrowings with Korean phonetics applied, while others evolve into entirely unique phrases that can baffle even native English speakers—some require a few leaps in logic to understand.

In fact, Konglish is now so ingrained in the language that even native Korean speakers are sometimes unaware they’re using English words, albeit with Korean adaptations.

Some Konglish examples (of hundreds)

핸드폰 (Handphone)

A mobile phone or cell phone. While “handphone” might seem logical, it’s not a term native English speakers actually use.

아파트 (Apartment)

Refers specifically to high-rise residential buildings in Korea, which are a cultural phenomenon in their own right. And now it’s the world’s most-listened-to songs.

샤프 (Sharp)

Refers to a mechanical pencil. It’s derived from the “Sharp” brand but is used universally for all mechanical pencils in Korea.

노트 (Note)

This means a notebook or notepad, not just a singular note.

원룸 (One Room)

A small studio apartment. It sounds straightforward but is very specific to the Korean concept of a compact, single-room living space.

아이스크림 (Ice Cream)

Pronounced a-ee-seu-keu-reem, it’s the Korean phonetic adaptation of “ice cream” but is used universally for frozen desserts.

콘도 (Condo)

Refers to a vacation rental or resort, quite different from how “condo” is used in English.

매직 (Magic)

Refers to a permanent marker derived from the brand “Magic Marker.”

서비스 (Service)

Means “something free” or a complimentary gift, commonly used in restaurants or stores.

쿠션 (Cushion)

Refers to compact cushion makeup, a wildly popular Korean innovation, rather than an actual cushion or pillow.

And the list goes on.

Get out there and learn

If you have any questions about what it means to really learn a language, ditch the polyfluencers and drop me a message instead.